The construction and operation of buildings is responsible for approximately half of carbon emissions according to the UK Green Building Council. This opens ups the possibility for the Passivhaus to play a big role in mitigating the potential impacts of climate change. Passivhaus, a fabric first architectural method characterised by strict performance-based standards developed by the Passivhaus Institute, is a powerful method that could radically reduce the energy a building uses.

First developed in Germany in the 1990s, there are today 65,000 Passivhaus buildings worldwide built in over forty countries. Early examples have typically been individual houses, but in more recent years, there has been a steady but gradual pushing of boundaries in the size of Passive buildings. With this in mind, Allies and Morrison has embarked over the last year on a research project to determine how tall one could push the Passivhaus standard, collaborating with colleagues at the Passive House Academy, engineers Buro Happold and cost consultants Gardiner and Theobald. The goal of our research has been to design tall Passivhaus building - a Passivtower - which could offer a high density low-carbon housing solution for cities.

Why tall buildings?

London, in particular, is undergoing a boom in tall buildings - especially in the residential sector - making it an ideal testing ground for this idea. This year's NLA Tall Building Survey finds that there are 455 tall buildings currently planned or consented in the capital, which 'have the potential to deliver an estimated 100,000 new homes'. As the London housing market looks to tackle the ongoing housing shortage, could high density residential offer and opportunity to upscale Passivhaus?

Our research suggests that it can.

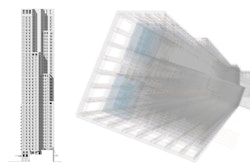

We undertook a feasibility study to RIBA Stage 2 for prototype tower of 48 levels of residential accommodation with a mixture of 335 3-, 2-, 1-bed and studio apartments, which meets the Passivhaus criteria. If realised, it would present a world first as the Passivhaus standard has been been attempted at this scale before and would be the tallest Passivhaus building in the world.

Business as usual vs Passivtower

We began by designing a 48-storey residential tower as we would do usually, to a strong environmental standard able to achieve Code for Sustainable Homes Level 4+ and BREEAM Excellent ratings. The building had a treated floor area of 25,000 sqm, a building envelope of 67,000 sqm and a thermal envelope of 20,500 sqm. Through the existing database of Passivhaus buildings, we then reviewed a series of medium density Passivhaus schemes throughout Europe to generate an approximate version on building u-value (the measure of its insulation), airtightness and performance levels that would likely be required to upgrade our tower to Passivhaus. Using the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) software, we were able to test the 48-storey tower to see if it could achieve Passivhaus criteria without significant changes to the tower's architectural quality. Buildings that meet Passivhaus criteria have a highly insulated continuous external envelope, carefully balanced glazing specifications to capture solar gains and an airtight fabric. Thermal bridges are mostly removed and heat recovery efficiency is exceptionally high.

Designed to these standards, the tower would see an 18.3% reduction in cooling energy demand, 18.4% reduction in primary energy demand and a dramatic 82% reduction in heat energy demand with plan layouts for individual units relatively unchanged. The heat gains of just one Passivhaus tower would equal those of more than five 48-storey towers built to baseline standard. Prominent buildings such as London's own BREEAM 'Very Good' City Hall would emit 5.9 times more carbon emissions even though it is a smaller building, having 80% the treated floor area. Against business as usual, the Passivtower would achieve a 65% reduction in heat energy generated from solar gains, 60% reduction in glazing heat losses, 85% reduction in ventilation heat losses and an 81% reduction in thermal bridge heat losses.

Achieving architectural quality with exemplar building physics

We set out to produce a beautiful architectural result as well, which at the outset we hoped would be achievable as by their very nature, Passivhaus buildings have a particular focus on construction quality. The design has a refined and straightforward composition with a stepped massing that helps to humanise its scale, creating terraces - or outdoor rooms - that are sheltered from the wind. A relatively high glazing percentage in the building envelope could provide generous natural light and views for all new units. The facade would be accentuated by deep window reveals and a grid of brick finished GRC panels. The option to explore alternative materials for the building envelope would be possible depending on local climate and context.

Another core objective of this project has been to generate a greater understanding of building performance at this scale, to London's 2025 estimated climate conditions. Aside from the fact that cooling demand, the total internal heat gains is perhaps the most surprising finding. Through the transparency provided by the detailed PHPP figures, we were able to establish that over 50% of the building's heating requirements would be supplied through a combination of appliances, people and domestic hot water pipe work. We were also able to generate considerable data on the importance of glazing specification, airtightness levels and the removal of thermal bridges - and developed strategies for achieving these.

Passivtower a solution for the low carbon city?

Passivtower's potential

The concept of sustainability through density is not a new one. In London in particular, as the housing market looks to tackle an ongoing shortage, building at scale addresses many of its inherent financial and sustainability challenges. The Passivhaus standard has been been attempted at the scale proposed, however, as our findings highlight, it could be argued that the sheer scale of the proposal reduces many of the traditional challenges associated with Passivhaus. The repetitive nature of high density residential buildings allows for increased use of modular construction and greatly reduces risks associated with ultra low airtightness levels of a building such as the Passivtower. In achieving Passivhaus across large scale developments, the potential to decentralise energy supply grows exponentially. With entire neighbourhoods being built in London today, could these offer opportunities to test Passivhaus at a wider scale?

One potential drawback is the perceived expense. When considering an apartment that uses 80% less energy than a typical London new build, how does on incentivise a developer to invest in the Passivhaus standard when the benefits are passed to the purchaser? One obvious route is to introduce the Passivtower in the Private Rental Sector (PRS) where the developer retains a vested interest in the building over its life-cycle, there would be an incentive to build a tower that is resistant to fluctuating energy prices. But in scaling up to 48 storeys, the rental revenue uplift would not hold the same value as the height of the apartment increases. So what then?

A potential solution could be the development of a hybrid model which entails outright sale of an apartment to the buyer with energy supply, maintenance and operations remaining with the developer. This novel approach would allow the developer to sell heating and cooling at reduced market rates while profiting and also gaining new efficiencies through centralised MVHR systems. Projects such as these would become attractive to investors such as pension funds as it appeals to their need for long-term investments. The Passivhaus standards' emphasis on material and construction quality would also help to keep long-term maintenance costs down. What this signifies is that the Passivtower could be not just a way to reduce the ecological footprints for a global city with a growing population, but also an attractive delivery method for a city facing mounting challenge to its housing supply.

Discover the full article in PDF