Urbanising infrastructure

While buildings can often last years, the traces left by infrastructure can last centuries. The life of many cities in the twenty-first century still relies on Victorian train networks, the bridges and pumping stations of Brunel and Bazalgette, or the high roads laid down by the Romans in the first. This suggests that a long-term view is needed.

Fundamental decisions regarding infrastructure often define the working and future of cities: where to put underground lines, how to lay new streets bringing services to new neighbourhoods, where to place electric substations or metropolitan sewage. On many occasions, architects are not involved in these decisions, but challenges that might be understood primarily in terms of engineering can benefit greatly from urban thinking.

Masterplan proposal for railyard overground development, Queens, New York.

York Central

Reconnecting a city

York Central is a rare site. Prior to the birth of the railways, the area was largely agricultural, in the shadow of the walled ancient city of York. By the mid-1800s, industrialisation and trade fuelled the growth of the city, and this previously agricultural landscape was cut through by now disused train sidings, railway track and coach sheds. Yet York today is a much bigger place. Its population in 1850 was approximately 40,000, by 2010, it was 200,000, but this now prime site, adjacent to the ancient centre, remained empty and physically detached from the city that grew up around it. Our masterplan is guiding its integration into the fold of modern York. Care has been taken to design new connections with surrounding communities.

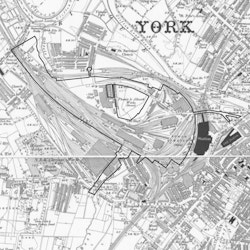

Site boundary and railway yards, York

Following bomb damage endured in the Second World War, and in an era where the automobile was ascendant, a multilevel ring road was built around Coventry in the 1950s. Its unintended consequence was to divide the city’s core from its outer parts, including its railway station, causing lasting damage to the fortunes of the city centre. Overcoming this barrier has been central to the commercial viability of the masterplan for Friargate, a new city quarter. It gives the ground level back to people. New direct north-south routes breach the ring road and a new Station Square all help to direct people more easily, by foot, into the city centre. And for those arriving by rail to Coventry, it provides a friendlier welcome.

Friargate Masterplan, Coventry

The first completed building of the Friargate masterplan and a new route reconnecting Coventry Station to the city centre

Because of its topography, and its complex overlay of industry, transport and utilities, the site of London's Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in east London's Lea Valley was immensely difficult to assimilate and understand.

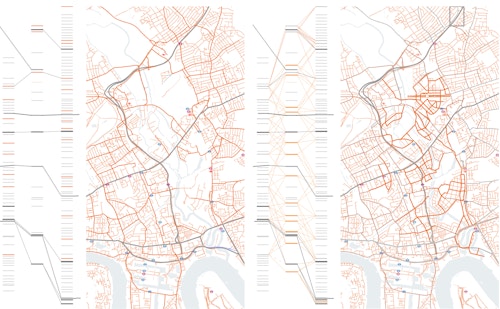

Lea Valley, east London: stitching together the city

The two drawings illustrated above were produced to expose the difference between the frequency and variety of east-west vehicular and pedestrian routes in the established urban areas on either side of the Lea Valley and the relative paucity of those present in the valley itself. The illustration of the inherited condition reveals a significant divide through east London. The second illustrates the scale of the transformation – and in particular the number of new bridges that would be required – if the Lea Valley were to be provided with the same degree of urban permeability as the more mature – but by no means perfect – pieces of city on the either side.

Installation of new connections across the valley

Bridge, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

Infrastructure as cinema

The redevelopment of King’s Cross has involved incorporating a significant quantum of new development into a site defined by two of London’s busiest railway stations. It also has required the insertion of new infrastructure to service new development and facilitate connections.

Those arriving by train may notice a curved wall of metal bars alongside the tracks just before pulling in. These 6-metre high fins conceal the centralised cooling energy generation plant for buildings within King’s Cross. Vertically arranged fins set up a diagonal inflection, from fully light to entirely dark, they have the appearance of dynamically (and rapidly) changing as one moves past them. The effect is like an animated flipbook making visible what would otherwise be background, or even invisible altogether.

Elsewhere in King’s Cross, a curvilinear underground tunnel connects passengers walking from King’s Cross-St Pancras stations to Pancras Square. A 100-metre long light wall traverses one side of the tunnel, turning it into a canvas for a variety of art and multicolour light displays with many personalities: a backdrop for fashion shows, lit up in the rainbow colours during London Pride, an object of fascination and a big hit on Instagram. It’s more than a tunnel.

King's Cross Cooling Pod

Infrastructure has duties beyond its immediate practical role: to work with the urban grain and to contribute to the intrinsic vitality of city life.